Process

This is a short film made during a commission I worked on for one of the UK’s leading global luxury car brands.

Glassblowing is a craft unlike any other - the material changes state during the making of a piece which is quite mind-blowing when you think about it. You start with a molten liquid, and by the end of making, that liquid has cooled to become solid. The other unique aspect of working with hot glass is that you can’t actually touch the material you are shaping. It takes many hours of practice to begin to feel in control of this magical process. Hopefully this page will give you an insight into how I make my work.

I love the fluidity of hot glass, especially lead crystal. It’s a very graceful material. By applying a combination of heat, hand tools, gravity and centrifugal force you can encourage it to do what you want, but it doesn’t always want to co-operate! Glassblowing is physically and mentally challenging, especially when you are hiring by the day. This means production is limited to a handful of pieces in a day. I hire a studio to make my work which means the pressure is on time-wise, but on the plus side I’m not paying the bill to run the furnace - which is on 24/7.

The glass is kept at 1100 degrees C, in a gas-fired furnace. The furnace is kept at this temperature constantly, apart from when new glass (broken pieces called cullet) are added at the end of the day to refill the pot. The temperature is raised overnight to melt the cullet.

The reheating chamber or ‘glory hole’ is used to keep the piece warm during the making process, and to direct the heat to certain areas. You need to ensure that the area you want to shape is soft enough to work. Glass becomes pretty solid when it drops much below 700 degrees C.

The final part in the making is when the piece is knocked off the pontil iron (pronounced punty). This leaves a mark on the base where a piece of hot glass has been used to stick the pontil iron to the base so the neck of the piece can be heated and opened. Some people grind and polish this mark away, but to me, this mark is indicative of the hand made process. I melt the pontil mark with a propane/oxygen torch to soften it. Then, to ‘sign’ the piece I have a bespoke letter R stamp, made in the exact font of my logo, so each piece has an R for Raven on the base, showing that it has been made by hand by me, with love!

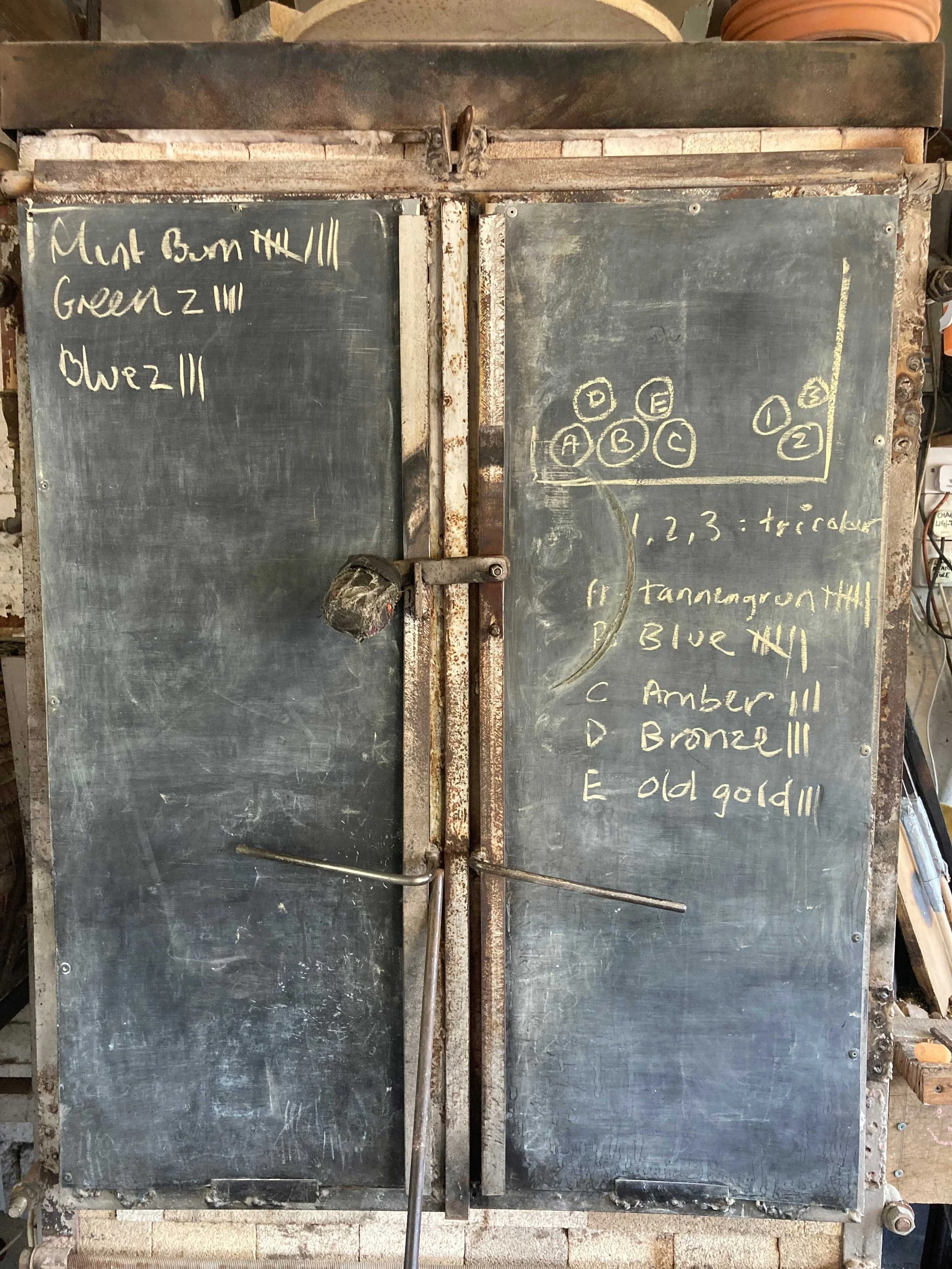

Once a piece is finished it is placed in the lehr (an annealing kiln) which is kept at 460 degrees and gets filled up over the course of the day (can you imagine how hot it is leaning in to put a piece at the back with some kevlar oven gloves?!). Eyebrows have been frazzled!

Opening the lehr the next day is always a thrill, and can be a bit of an emotional roller-coaster. It’s the first chance I have to hold the pieces I made the previous day, to feel their weight, study their form and see how they interact with light. Coloured glass often looks different when hot, so it’s also the first chance to admire whatever shade of colour things turn out to be.